Exploring Equitable Design

- Jesse Herrera

- Sep 25, 2020

- 12 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2024

After a short summer break, we resume our journey to find housing solutions for students experiencing homelessness. We reflect on the impact of the pandemic, pressing social instability over police brutality, and the looming threat of evictions for many households. We pick up the discussion on design equity to explore alternative methods that preserve the dignity of those we aim to serve.

Before we dive into the intricacies of design equity, we revisit our definition of homelessness. Given the impact of COVID-19 and the other pressing issues we have witness during our short break, we respect that homelessness not just a lack of shelter, but a lack of a support system. This serves as the basis of any solution to college homelessness and guides our discussion into equitable design. We understand that a support system manifests itself in several different ways, including our laws and societal structure.

Dr. Sarah Urquhart kicks off our discussion design equity by introducing us to Athena. Athena shares many similarities with what we come to associate with the student journey. Bustling through her classes, working hard to ace her test, and rewarding her efforts with a vibrant career. Athena as we come to know is different. She struggles to simultaneously manage a job, school, and her personal life. Entrapped in her own struggle, Athena found herself living in her car and having to shift her priorities constantly between having a meal, getting enough sleep, and completing her studies. Athena, much like the goddess of wisdom, was able to overcome her challenges, complete her education, and get into a vibrant career.

Athena as we learn, is a student that is encountered on multiple occasions. Most though do not get to revel in overcoming impossible odds. Many fall short, entrapped into in the jaded reality that a minimum wage job and a deficit of hours bring with today’s struggling college student. Accumulatively a student needs 129 hours per week to study, sleep, eat, and maintain a healthy living. However, given the current minimum wage, which accounts for many of the jobs available to a non-educated worker, a student needs 208 hours to learn and pay rent simultaneously. When we account that there are only 168 hours in a week, this leaves a 40-hour deficit that comes out of time to rest, study, or eat.

Combined with the financial burdens of day to day college living, this reminds of the current reality Athena faces. If college students cannot satisfy their basic needs, how can they be expected to perform well in school or achieve their career goals? If there is not equity in society, how can there be equity in design? With clear deficiencies in basic instinctual needs in achieving Maslow Hierarchy of Needs, this question becomes critical aspect to explore as we embark on our journey.

Equitable design is “giving people the tools they need to be their best and authentic self, improve life expectancy, outlook and quality of life”

Antionette Carrol, CEO Creative Reaction Lab

Equitable design is a bridge to help us navigate the complexities of these issues. We cannot solve this challenge with a one size fits all solution. Equitable design is about creating solutions that meet people’s individual needs. It requires becoming intimately aware of the challenge and those that we aim to serve. However, we have to honest in recognizing that as designers, we can not be everything. We cannot provide direct service to aspects like healthcare or education as designers. We must work within the system to identify and align to existing resources. Equitable Design helps with identifying the unserved gaps and honing our approaches to achieve our overarching goals.

The benefits of equitable design start with the individual but have broader regional impact. We lose over 200 million people with superior intelligence due to environmental conditions. Given that over 70,000 of these people could be making Einstein level discoveries, it stresses the importance of alleviating the day to day worries over food, shelter, and safety. Diving deeper, we explore the potential of equitable design to break and prevent the cycle of challenges like homelessness. In the example shared we examine the traumatic effects of homelessness and severe insecurities to inflict other conditions such as PTSD, alcoholism, and mental illness. The decisions that often need to be made can put students on the wrong side of the law. Many could see their journey ending, when has barely started.

We shift to explore the importance of the team. As we have reflected many times, the premise of social work often leaves many voices from the table. As designers we have to be honest in recognizing that we are not experts in any one field. Our superpower, if we may call it that, is listening and facilitating. If we need solutions outside of our privy, then it pays to broaden our team and invite additional perspectives. We should not try to be pseudo experts and assume solutions. Most importantly, we must strive to build open participation with those we aim to serve. This idea is not new but given the severity of the entrenched issues we face; its relevance cannot be understated. It is important that we base our solutions on solid knowledge.

We aspire to do amazing work, however given the insecurities of day to day living, our capacity to contribute as a country is severely limited. Selling our designs and putting up pretty pictures is easy. As we learn, the practice of design does not necessarily encourage equity. Curiously, we explore how we might create incentives that favor equitable design practices. One barrier Dr. Urquhart identifies is the intellectual property model of design; a model in which some information is either unavailable or heavily restricted to the public for the financial gain of a small group of people. This inevitably creates a barrier of entry into the design process as well as an exclusionary atmosphere surrounding design as an industry. The intellectual property model of design usually takes the form of restricted software, restricted access to design teaching, and restricted access to the latest research.

Contrary to this model is the open science model of design; a model that is characterized by freedom of information, access to design tools, and open communication. As we learn, the open science model allows for greater transparency and accountability in delivering methodologies. It would allow work to be documented and open to peer review, aiding in building a collective and trusted resource pool to utilize. This collective knowledge would help future problem solvers have better information to build better solutions, aiding in achieving some of the current and future grand challenges for society. There are some aspects of open science that warrant further investigation, but it is a framework design should engage in and experiment with.

There are some examples in the design industry such as LEED with the US Green Building Council (USGBC). However, with LEED the explicit details of the project happen behind closed doors and the process comes with heavy cost. It prohibits a firm from building off the insights of previous projects. This can limit participation in projects and hinder the ultimate goal of reducing carbon emissions. Granted, this process does generate revenue for the USGBC, it falls back on the framework not providing incentives for equity.

As romantic of idea the open science model is, it is not commonplace. Companies for the most part do not participate in an open science model because it hinders profitability. Knowledge in the Intellectual Property model becomes a protected asset to help the company. The Intellectual Property model allows firms to capitalize on recognition which can fuel the rise of star companies, which will lead to increased profits. However, it also means the company is stuck in their own process and has to spend resources constantly inventing and defending patents. For clients, the Intellectual Property model can come at extreme cost. In a specific example, most building automation companies (fire alarm, HVAC, electrical) have proprietary rights on their software and hardware. Once a system is installed, the client must pay a reoccurring fee to keep the system. If for any reason the cost become to extreme or the system does not perform as expected, the only option usually available to a client is removing the infrastructure in its entirety and replacing it with a new system, which can be very expensive. The fallacy remains in the Intellectual Property model, as any new system installed will be carrying the same issues.

For society, this creates a conflict, as the knowledge or technology needed to solve problems is restricted. This has magnified problems as we enter the age of Smart Cities and leaders entertain the datafication of infrastructure and operations in urban centers. There are hefty debates on who should own the data, what it should be used for, and what data should be collected. Looking outside of the design industry, examination of the software industry has shown how the open source model has been used to increase the quality of their products and allow a diversification of skillsets. WikiHouse has also been experimenting with an open sourced design platform to aid in the localized manufacturing of individual houses.

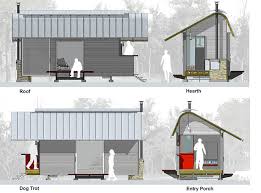

We move to exploring the balance between impact and feasibility, bringing us to a recent cottage community project, Tiny Victories. Designers were given the opportunity to create a community of tiny houses for the homeless community in Austin, Texas which started out like many social projects as a competition. Often in this model, architects must design based on assumptions on what an individual experiencing homelessness would need, which can only take the design so far in its’ capacity to serve. The architects who worked on this project experienced this firsthand with the completion of the competition. The products developed were architecturally relevant but did not meet the needs of the residents that well. For round two they scrapped the competition and instead aligned architects directly with individuals experiencing homelessness to discuss their needs and give them a voice in the design process. This approach was very well-received, and the architects reflected on the rarity of being able to meet and work together with the end user. This is common in mainstream practice. Rarely do designers, especially in massive housing projects, meet the tenants that will inhabit their spaces. When working with vulnerable communities, this aspect of design ignores the individual needs and can lead to exclusionary environments.

For Tiny Victories, the solution for round two resulted in intentionally undesigned spaces that allowed the individuals to make the space their own. However, this solution is not unique. In Chile, Alejandro Aravena, delivered a similar design to serve a low-income families. His firm embraced a participatory model and engaged directly with the families the project was aiming to serve. It plays to the importance of engaging the communities that are being served. In addition, an open source model could help organizations like Tiny Victories in sharing valuable insights so we can build off of previous models. That stated, it may not always be feasible for large-scale projects to work with every single resident, but there exists a balance between no interaction and total interaction that is largely unexplored in design. The development process often does not put future residents in contact with the architects. We believe that working directly with those who benefit from our work is crucial to the design process. It might allow us to create new iterations that could better serve the tenant and the developer.

Tiny Victories has heavily influenced my (Logan Rogers) development as an architecture student. Their results were so promising that it prompted me to further explore the impact that an architect could have on homelessness. While their findings are incredibly important for developing a solution to college homelessness, it is my goal to take their model and explore how we might optimize it for a much larger scale of impact.

Is there an added or hidden cost to doing or not doing equitable design? Simply put, yes. We have been paying the cost of inequitable practices through increased tax dollars in support programs and medical facilities. More so, we pay for this in increasing severity of mental illness, the loss of potential in our future leaders, and ultimately in the loss of life. If we do not practice and promote equitable design, we will ultimately repeat the same processes that led us to where we are now. If we want to eliminate and further prevent college homelessness, we must make it easier for everyone to participate in the design process. Furthermore, we must rethink our frameworks to ensure we have the toolkits necessary to solve societies most entrenched challenges.

Moving into the discussion portion of the forum, participants are prompted with the question, “How might we apply design equity principles to developing affordable housing for college students experiencing homelessness?” This question solicited a wide range of responses, but the conversation always came back to a few key ideas.

It became clear that the open source model of design appealed to many of the participants. Most agreed that financial and professional barriers around design information was not conducive to equity. It was also clear that, while efforts to eliminate immediate issues is worth our time, we must focus on the deeper systemic solutions to the issues of college homelessness and design equity.

We explore some local examples of institutions including Amarillo Community College, that have adopted a student centered framework to better address the increasing rates of poverty and homelessness their student body faces. Although not perfect, it stands out as a model other institutions can draw lessons from. Particularly unique is how they engage students on a regular basis to identify gaps and solutions. Some of the solutions could be subtle tweaks to the food pantry to allocating funding to pay for a hotel stay. The framework allows the college a nimbleness that is needed when dealing with imminent barriers. Within this framework, we resonate with the idea of expanding the team and building more effective collaborations. We are curious on what some key steps may look like to establish a more stable environment for students and going beyond just the shelter needs. It raises the importance on getting a better grasp on the student narrative.

We had an opportunity to discuss the potential of investing in life skills at an earlier age. Life skills or family consumer sciences as they are now currently referred as, are usually the first programs to get cut. There is a teacher shortage in these fields which hinder these programs. We are cautioned to consider that education is not a silver bullet. Even with better education programs, there are still abundant environmental challenges that need to be addressed. Any attempt to ignore that fact contributes to the pressing realities we discussed prior.

Several of the architects in our discussion mentioned the issue of getting investors for equitable projects. Investments imply a return on investment, which is difficult to acquire when a project does not generate profit. It was noted that architects could find more philanthropic investors if they had more established connections to investors. This is a common problem among smaller architecture firms that are more likely to do community-based work but are beholden to what the local developers are willing to work on.

As someone who is studying architecture (Logan Rogers), I can attest to this grim reality. Architecture is often decided by those who have power, and our design becomes a manifestation of their power. This point intrigues me, because no matter how equitable the design process is, it still needs to be funded by someone who usually has a different plan; the issue of design equity quickly becomes an issue of cultural and societal equity. We must look at this as an equation. By the time the project reaches an architect’s desk, the formula is filled, and the output is pretty much determined. It becomes hard for the architect to be the apex in this process as their role completes only a small part of the equation. If we are to better address this there should be resources that designers can leverage to have more say in the funding and development of their project. We ask how we might shift the power dynamic, so designers are not so powerless to influence change?

Another idea shared explored the potential of using technology to connect generosity to a need. Purposity which acts as a social media network helps align generous community members to individuals in need. It is a subtle way to individualize giving. In a similar vein we discuss the idea of aligning students to senior citizens. There have been successes in with Nesterly and HiLois in creating digital platforms to help facilitate this. Locally, Shared Worth is working to develop a similar program for Tarrant County residents. On a broader spectrum organizations like North Texas Community Foundation (NTCF) provide similar charitable services to communities in the region. Through North Texas Giving Day, NTCF provides donors a platform to support causes that most resonate with them. These organizations are templates that our industry could use to create an online community of designers, professional architects, and developers who are interested in creating more inclusive spaces, bridging that gap between generosity and need in the field of design.

So, where do we go now? CoAct is committed to creating community-based solutions that last. We believe this can only be done in a collaborative effort, being sure to include everyone in the discussion. This forum served as a critical discussion of research and ideas that will inform our application of design tools to solve college homelessness. Following this discussion, we plan to meet with a committee of students to gain valuable perspectives on the homeless student condition. As we wrap up our series of forums and conclude our research, we enter the concept development stage of the project. Our aim is to develop a prototype that will allow us to test our theories and lay the foundation for future work. With the insights we gained today, it is imperative that we create an open sourced toolkit that we can share to help others replicate and improve the models we develop. Before we do, we must be sure to explore as many perspectives and ideas as we can, which would not be possible without the participation and passion of everyone who has helped us. Our thanks go to our participants and again to Sarah Urquhart for sharing their thoughts on this pressing topic.

Together, we will address college homelessness

Written by:

Jesse Herrera | Executive Director | CoAct

Logan Rogers | Project Coordinator | CoAct

Comments